For the last fifteen weeks, I have been slowly tearing down and rebuilding my schedule and habits to support the style of work that Cal Newport describes in his 2016 book Deep Work: Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted World. Although this is the first time I’ve read the book, I’ve been familiar with Newport and his ideas about learning and productivity for several years. When I was an Instructional Designer at a coding bootcamp, I read Newport’s Study Hacks blog and created student materials to help people use Active Recall while studying. When I was learning to code, I set aside time each week to engage in Deliberate Practice, a study technique made popular by Newport.

Before reading the book, I knew that deep work was a way to quickly learn and master new things by honing, as Newport says, “the ability to focus without distraction on a cognitively demanding task.” While I understood Newport’s definition, I learned a lot from the first part of the book which lays out some philosophical arguments for pursuing this level of focus. In Part I, Newport explains why learning how to engage in deep work is in the reader’s personal and financial interests, but the argument that resonated most with me is that the quality of your life will be better if you engage in deep work because when you consistently grapple with hard problems you will increase your rate of intellectual and spiritual growth. Although much of the book focuses on techniques to increase the number of things you produce, Newport repeats this line several times: “A deep life if a good life,” and after experiencing the kind of repeated, focused attention he describes, I agree.

As I read Deep Work, I found that the ideas in the book were in conversation with some of the work and study habits I’ve been cultivating the last decade of my life. In 2010, I began my first year teaching special education, as well as enrolling in a full-time graduate school program. This was the busiest phase of my life, and I started using the Pomodoro Technique to manage my time and to artificially juice my motivation to write lesson plans for my students, and papers for my professors. In the last five years, I have studied A Mind for Numbers by Dr. Barbara Oakley who describes the difference between focused and diffuse thinking, and study techniques that leverage both modes of processing. In spite of the habits I had already built, I have struggled to devote time during and after work to be who I want to be: a reader thinker, hacker and writer, and I’ve been pleasantly surprised at how much more I’ve been able to do since applying the lessons from Deep Work.

My Approach to Deep Work

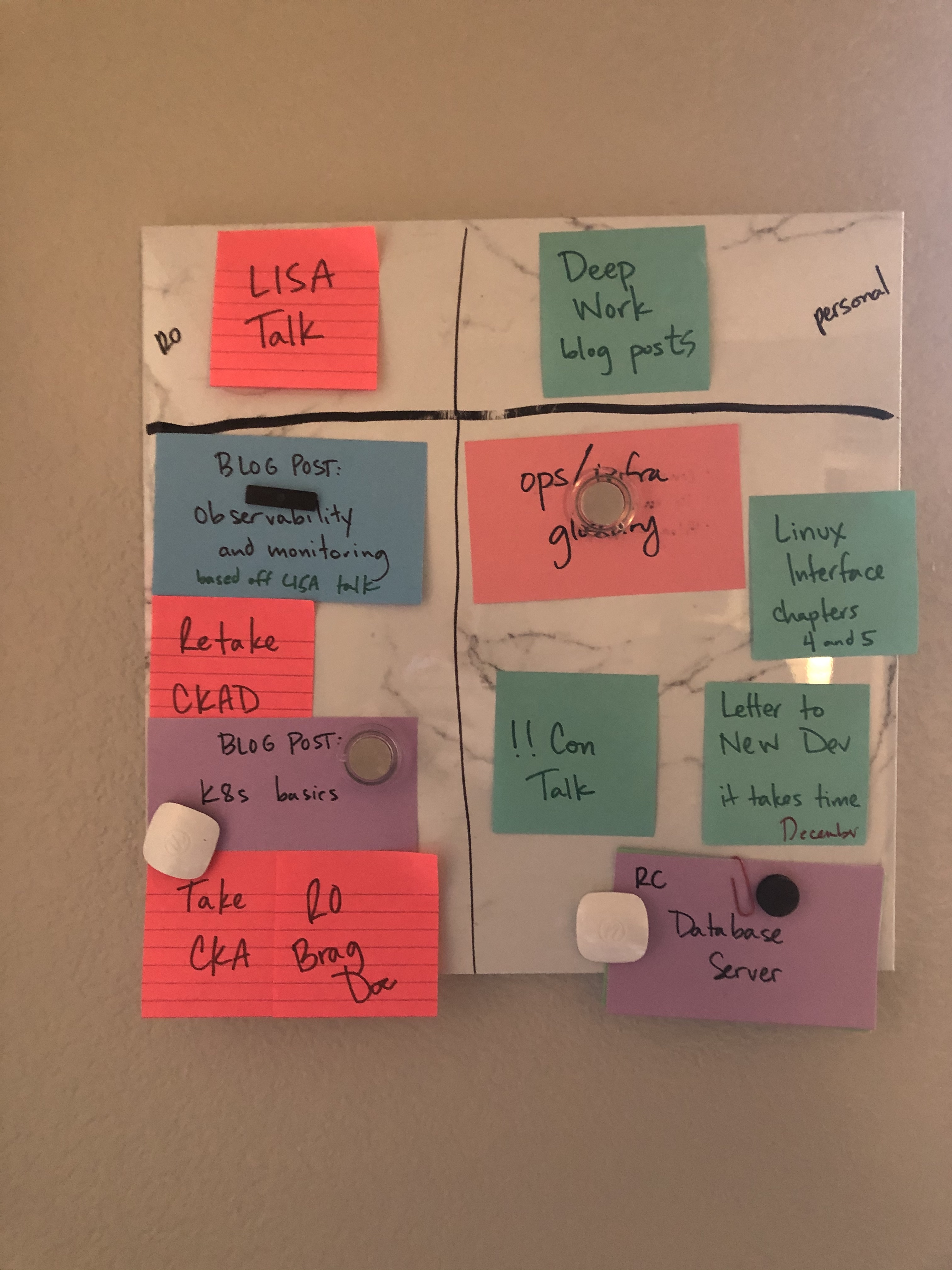

I started by identifying the projects I wanted to complete, writing each one on its own sticky note, and posting them on a bulletin board near my desk. Below is a picture of that board which has my work-related projects on the left and personal projects on the right.

Alt text: A bulletin board with a list of Kim’s work projects on the left which include LISA talk, write a blog post about monitoring/observability, retake the CKAD. The right includes a list of personal projects like write Deep Work Blog posts, ops/infra glossary, Linux Interface Chapters 4 and 5.

Personal Projects

A few weeks ago, I listened to an episode of the podcast Hello Monday which featured writer Elizabeth Gilbert. Halfway through the interview, Jessi Hempel, the host, asked Gilbert how she structures her day in order to do her best writing. Gilbert responded by saying everyone has a time of day when they produce their best work, and in order to make use of that creative time, “You take that hour and you put a border around it and you say that this one belongs to you and then the 23 other hours of the day, give your second best to everybody else.”

This advice was a revelation to me. My best hour is first thing in the morning, and until I heard Gilbert’s recommendation, I was using this precious time to do frivolous tasks like reading emails or skimming news articles on my phone. Since then, during the week I’ve made it a habit to get up, make myself coffee, and use the first 30-60 minutes of my day to do deep work on my personal projects. I’ve also committed to taking a day off at least once every three months to experiment with longer blocks of undistracted concentration. Finishing reading Deep Work and writing this blog post were my first couple of personal projects, and I’m starting to enjoy the process of reading and writing without distraction.

At Work

I am a Site Reliability Engineer which means I spend most of my time at work configuring cloud computers and writing software. My job is structured so that I have many opportunities for deep work; I work from home, I don’t have a lot of meetings because I’m not in a management role, and I get eight hours a week to work on projects of my choice. I am lucky that my company supports deep work, but even with these conditions, I have struggled to set aside time to focus on one just one task or problem.

One issue was that I needed support from my colleagues to feel okay about logging out of Slack, our primary tool for communication and my distraction of choice. I talked with my manager and the VP of Engineering at my company and told them I was reading Deep Work, and asked if a few times a week I could disappear from Slack. They said yes, and since then, 2-3 times per week, I schedule deep work sessions. When that time arrives, I let my team know that I’m doing some ‘heads down’ work, and that I’ll have Slack closed for the next couple of hours.

My Experience of Deep Work

Since I’ve started deep work sessions for my personal projects and at work, I’ve discovered some unhelpful habits that lead me to find something to distract myself from the task at hand. For example,when I experience an emotion that makes me uncomfortable, I will reach for my phone, look at Twitter, or check to see what new messages I can read on Slack instead of recognizing and acknowledging the feeling. My first several attempts at deep work made me squeamish, and I would quickly end the session by turning to one of my tools for ignoring my feelings.

I have a regular meditation practice, and earlier this year I took an online course called Mindful at Work, which taught me some techniques for recognizing these feelings, naming them and letting them be without trying to force myself to feel something else. I have been making use of this strategy during my deep work sessions.

In addition to applying techniques from mindfulness meditation, there are two other strategies from the book that help me stay focused: embracing boredom and taking breaks from focus, not breaks from distraction. In the chapter ‘Embrace Boredom,’ Newport argues that you must become comfortable with the experience of boredom so that even when you aren’t actively reading, writing or typing, you still remain focused on the problem you are solving.

Practically, this means that when I am stuck or bored, I let myself lay down and think about the problem or take a walk to engage in ‘productive meditation,’ but I cannot use my phone or turn on a podcast, two things I reach for when I feel weird.

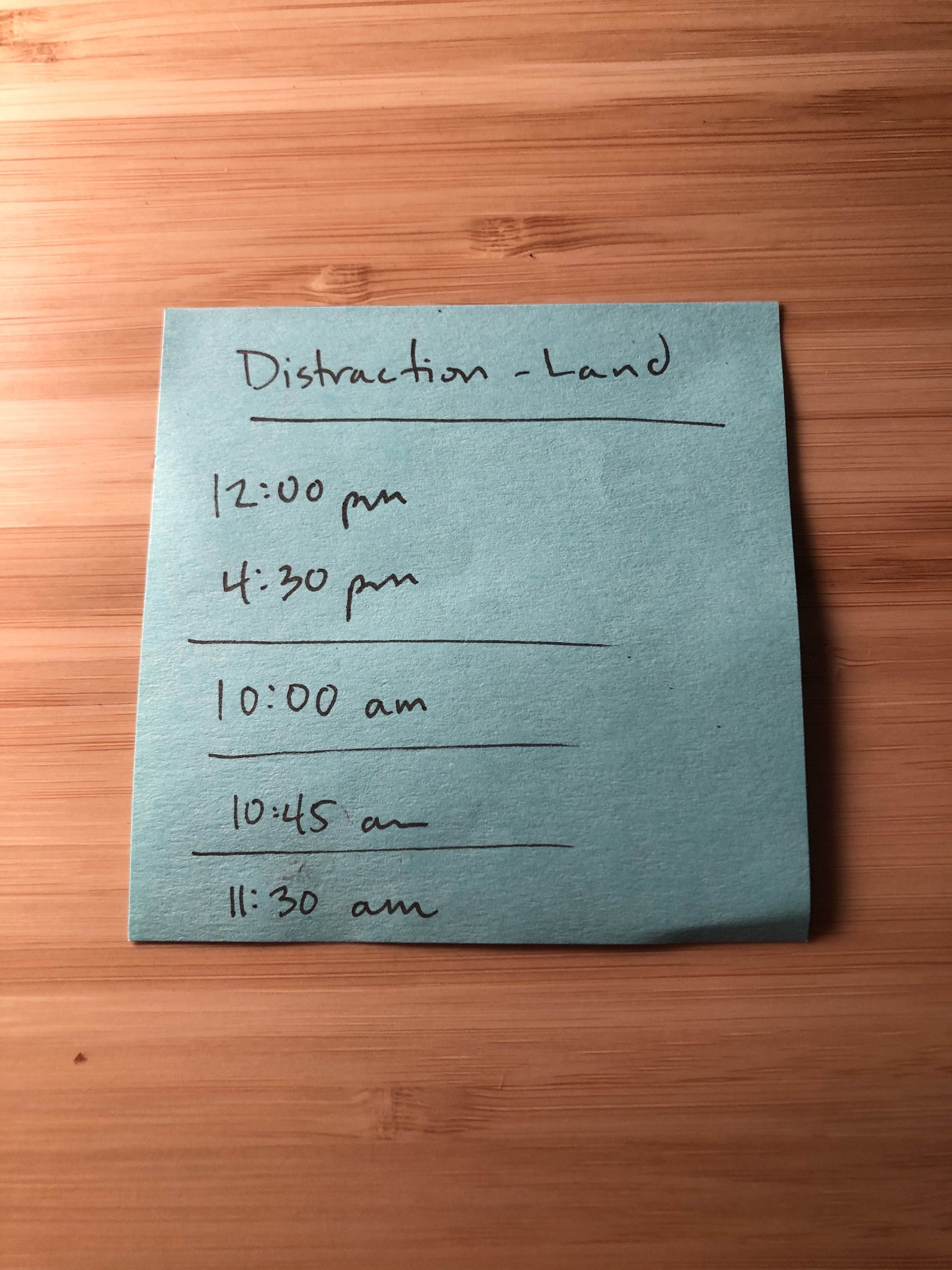

The idea of taking breaks from focus, not breaks from distraction is that you can shift your default mode to being one where you single-task, not multi-task with social media and instant internet access. Since this transformation, I have logged out of most of my Slack workspaces, as well as Twitter and Instagram, and I limit how often I look at the internet for fun. Slack, social media, and goofing off on the internet are still important to me, but I’ve started scheduling and writing down the times of day I can travel to what I call ‘distraction-land.’

Alt text: a blue sticky note that has ‘Distraction-Land’ written at the top, and a list of times: 12:00 pm, 4:30pm, 10:00 am, 10:45 am and 11:30 am.

Alt text: a blue sticky note that has ‘Distraction-Land’ written at the top, and a list of times: 12:00 pm, 4:30pm, 10:00 am, 10:45 am and 11:30 am.

The Result

Since I’ve started doing deep work blocks at work, the depth of what I learn and complete each day is greater than before. One way I can visually see this transformation is my ‘today I learned’ list. I try to add an entry at the end of every workday, and you can see that as time goes on, my entries are getting more detailed because I can research topics more deeply than I could when I was constantly distracted.

Overall, I have reduced the amount of time I spend on the internet, and I’ve also reduced the amount of TV I watch and have replaced it with reading. There are a lot of outstanding television shows, but right now, I’d rather read.

Another change I’ve noticed is that even when I’m not in a deep work session, I’m more likely to finish a task before moving on to another one. I feel more confident, and I’m completing the kinds of projects that I used to start, but never finish.

I’m not done applying the lessons from the book. Next, I will continue strengthening my ability to concentrate by memorizing a deck of cards or the memory palace technique, and I will try to lengthen the amount of time I set aside for deep work.

Although reading Deep Work changed the way I approach work and personal projects, I often wondered if it was really for me because nearly every example of someone doing something impressive as a result of deep work was a white man. The next project I’m working on is a blog post that is a critique of the lack of diverse examples in Deep Work.